Neckties made global news last week when Maori MP, Rawiri Waititi, was ejected from the debating chamber of New Zealand Parliament. He refused to wear a tie, evocatively describing it as a “colonial noose”.

It wasn’t that Mr Waititi eschewed neckwear. Rather, he explained that the traditional hei tiki — the greenstone pendant he wore instead — represented for him both a necktie and a tie to his people, culture and Maori rights.

In the intense debate that followed, ideas around acceptable business attire — long based on Western dress codes — were questioned against the expression of Indigenous cultural identity. Ties are now no longer required as part of men’s “appropriate business attire” in the NZ Parliament.

In Australia, Members of Parliament were allowed to ditch the necktie in 1977 when safari suits were officially considered business attire. Since then, however, Parliament House dress standards have informally shifted, with our male politicians uniformly donning ties in the chamber.

Ties have been tangled up in controversy here as in New Zealand. This narrow strip of fabric has many meanings for its wearers.

Read more: The tie that binds: unravelling the knotty issue of political sideshows and Māori cultural identity

From throat to groin

Shells, feathers, gold and fabrics have adorned people’s necks for millenia. The origin of the necktie is most commonly traced to 17th century Croatian mercenaries who wore cloth around their necks. One purpose was to protect the neck from the sword’s blade.

Cravats, draped or tied in bows, and “stocks” — a stiffened cloth that tied at the back of the neck — were worn in Europe for subsequent centuries, and by Australia’s early colonial administrators. They were made from lace, linen, silk and muslin.

The bow tie and the necktie — in a form recognisable today — were increasingly visible in the 19th century.

The tie’s symbolism attracts especially heated discussion around the styling of the masculine body. While the suit jacket creates a v-shape from the shoulders to the waist, the tie draws the eye from the throat to the groin — in the same way, some argue, as the codpiece did.

It has been suggested that this “overcompensation” explains former US President Donald Trump’s preference for long neckties, with one observer comparing them to the codpiece.

Read more: Research Check: do neckties reduce blood supply to the brain?

Tie-wearing in Australia

When Captain James Cook landed on Australian shores, he was dressed in uniform with linen tied at his neck — or so many paintings suggest.

Early administrators, too, wore crisp, clean neckwear, while convicts had a neckerchief issued as part of their uniform.

Influential Aboriginal people, meanwhile, were sometimes presented with a breastplate to be worn around the neck.

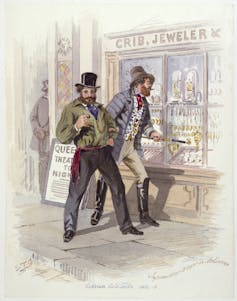

Artist S. T. Gill illustrated life on the Victorian goldfields in the 1850s, with some of his hard-working diggers tying handkerchiefs around their necks. But the wastrels and dandies he drew splurged on flash clothing including vividly-coloured silk cravats worn with gold pins in the style of gentlemen.

In the early 20th century, as manual workers removed their jackets and ties, wearing a three-piece suit and necktie become shorthand for authority and professionalism.

As the business suit became a menswear staple at the turn of the 20th century, the popularity of ties skyrocketed. In 1950, when Sydney’s Sun newspaper published the Everyman’s Ideal Wardrobe, the extensive list recommended 18 ties alone.

However suits and ties were hot, if not oppressive, as Australia’s climate “dress reformers” insisted. When Ray Olson photographed David Jones’ new season fashions in 1939, he captured two men in contrasting attire walking along a city street.

One wore a fashionable double-breasted suit, jaunty hat and close-fitting tie. The other was dressed in a short-sleeved shirt — without a necktie — and tailored shorts. Radical for the time, this look was adopted decades later, with South Australian Premier Don Dunstan leading the charge on relaxed dress standards.

In 1967, The Bulletin described Dunstan’s ensemble of shorts, long socks and a short-sleeved shirt worn without a tie as a “summertime example” for government and bank employees.

Skinny, wide, loud or patterned

As attitudes to ties have transformed across decades, styles have gone in and out of fashion. The skinny tie popularised by bands such as the Beatles in the 1960s was favoured by young Australian mods.

The wide tie, too, has had its moments. In the 1970s, loud, wide patterned ties were the height of fashion. For flamboyant politician Al Grassby, wearing wide colorful ties signalled a move to “a new colorful Australia”.

Read more: A scarf can mean many things – but above all, prestige

These days politicians might wear certain colours to mark their allegiance: the coalition has a widely commented on preference for blue, for example, though this isn’t always evident.

Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt often chooses a necktie with an Indigenous design to signal his heritage.

Ties do many things. Though they express identity, they can just as readily act as a “uniform” for their wearers. They give power to some, while taking it from others. Does Rawiri Waititi’s criticism of the “colonial noose” suggest Australia, too, might be heading towards a reckoning with the tie’s place in our history?