Can I choose what vaccine I get?

Australia’s keenly awaited COVID vaccine rollout begins today, with the ultimate goal of vaccinating all Australians by October.

Here are the answers to some key questions.

Can I choose which vaccine I get?

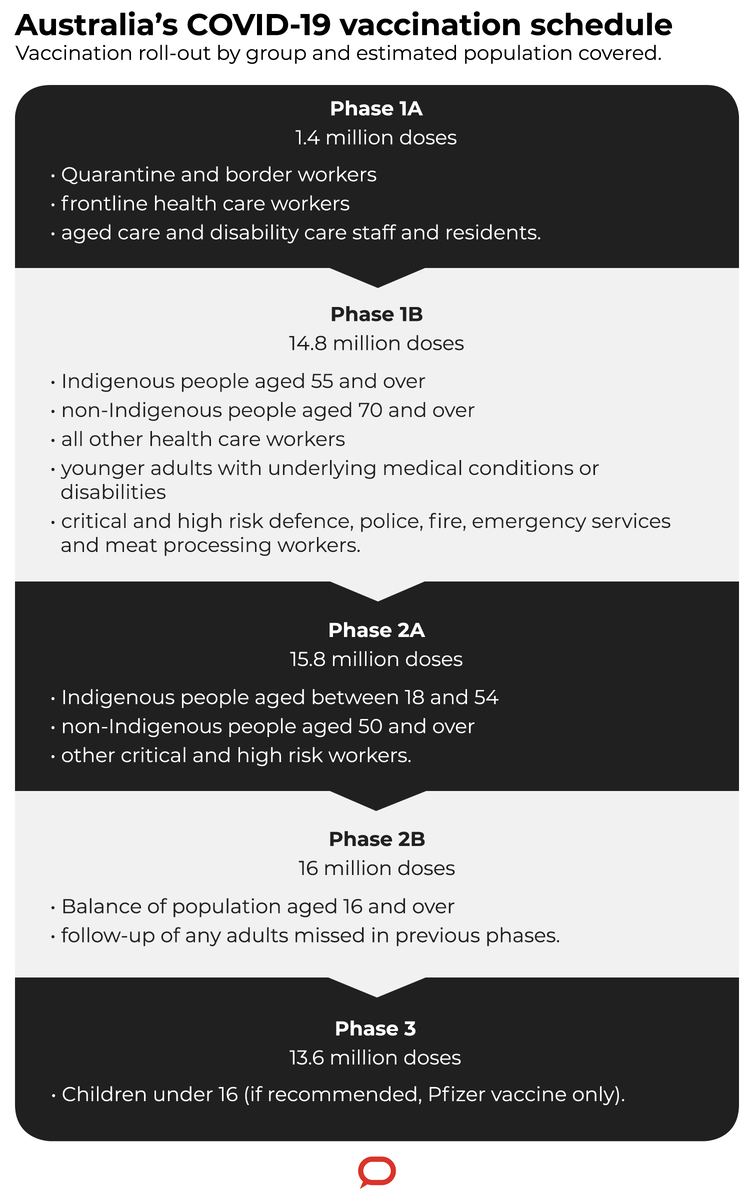

No, there won’t be a choice for the average person. The current initial rollout of the Pfizer vaccine isn’t enough doses to vaccinate all of Australia. So the first people vaccinated with the Pfizer vaccine will be frontline health-care workers, including aged care and hotel quarantine officers.

The AstraZeneca vaccine will be produced for the general public. It’s hoped that will be rolled out during March.

Forget Facebook and get your news straight from experts.

I can’t say how the logistics will run — that’s up to the government, presumably on a state-by-state basis. Most likely they will try to prioritise the highest-risk groups such as the elderly and people with chronic health conditions.

For most people it will be a case of waiting for further announcements as to when enough vaccine is available and it’s appropriate to make an appointment. Children are unlikely to be included in the vaccination program.

How will I be monitored for side-effects?

As doctors, when we vaccinate people we generally like to look after them for about 15-30 minutes, just to check they haven’t had an adverse reaction. That should be the practice for the COVID jab, just the same as for any vaccine.

For those 15-30 minutes you will generally just be sitting in a waiting area at the clinic. You will be monitored to see if you develop any symptoms such as hives or a rash, or wheezing. In those cases you would be monitored even more carefully and staff would take your blood pressure and pulse rate.

If you experience any symptoms once you’ve gone home, it would be up to you to contact your local doctor. Obviously, when trying to vaccinate 25 million people, health authorities can’t follow up with every individual. It’s very much up to them to follow up with whoever gave them the vaccine — whether their GP clinic or other health service.

Should I still have the vaccine if I have an allergy?

That needs to be a conversation between individuals and their doctor, who can advise on a case-by-case basis. But, generally speaking, there are no common allergies that should stop you having a COVID vaccine. If someone has a peanut allergy they can have the vaccine, and the same goes for shellfish, wheat, eggs or any other common allergies.

Some people are allergic to an ingredient called polyethylene glycol, or PEG, which is found in more than 1,000 different medications and is used in the Pfizer vaccine as a mechanism to help deliver the viral mRNA (genetic material) into your cells. In the US and UK vaccine rollouts, a very small proportion of people seemed to have an allergy to this compound: with a million doses you might see about ten people have this allergic reaction. It is rare, albeit less rare than allergic reactions to influenza vaccines.

But no one has yet died from being vaccinated against COVID, so these cases are being captured effectively and are generally detected within the initial observation period of 15-30 minutes. Severe reactions can be treated with an epipen; less severe cases are just monitored.

People might already know they’re allergic to PEG and they shouldn’t receive the Pfizer vaccine, but if they don’t know, there’s no way of knowing that in advance.

Read more: How the Pfizer COVID vaccine gets from the freezer into your arm

The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine doesn’t contain PEG. It contains a related compound called polysorbate, which appears not to trigger the same allergy. If you have a known allergy to PEG you would probably be given the AstraZeneca vaccine.

It’s important to stress that these compounds are not preservatives — they are mechanisms to deliver the vaccines effectively.

Will I be fully protected? Do I still need to follow COVID restrictions?

The two vaccines have different efficacy rates — 95% for Pfizer, 62% for AstraZeneca — but these refer to their ability to prevent infection rather than disease. The fact is both are very good at preventing serious disease.

This means that, although you may still have a chance of being infected, you are much less likely to develop severe symptoms, and therefore less likely to infect others. Someone with severe COVID might be coughing and spluttering and spreading the virus more easily, while someone without symptoms might not.

Bear in mind there are two main reasons for the vaccine rollout. The first is to protect members of the public from getting very ill or dying.

The second aim is to provide a degree of immunity in the general population that will ultimately stop the virus circulating.

Of course, this second goal is much harder, which is why it’s still important that we follow any and all COVID precautions. But the hope is that over time we’ll see fewer and fewer people who are COVID-positive, and the risk of spread will fall.

Will the vaccine last forever or will I need to be revaccinated in future?

The current COVID vaccines require two doses, several weeks apart. It’s very tricky to say how long the resulting immunity will last, because globally we have only had these vaccines in use since December or so. It’s possible the immunity might last a year or longer, but at the moment it’s unclear. People might well have to be revaccinated at some stage.

We’ll start to get that data soon though. In fact we should have plenty more information by the time the AstraZeneca vaccine starts to be administered in high numbers in Australia around June or July.

Will the vaccines work against mutant coronavirus strains?

In the fullness of time I expect we’ll start to see “escaped mutant” variants of the coronavirus that can evade the vaccine or make it less effective.

To an extent that’s happened already — the AstraZeneca vaccine looks to be less effective against the South African variant than against the other current variants. Having said that, although it’s not as effective at preventing infection, it still probably has a good chance of stopping you getting seriously sick.

Because we’re not vaccinating everyone in the world, there will always be a pool of people who can incubate new viral strains, potentially giving rise to new mutant variants.

There’s no doubt the vaccines will need to be updated from time to time to deal with this.

Thankfully this process will be relatively straightforward. mRNA vaccines such as Pfizer’s can be tweaked very quickly – virtually overnight – to accommodate new mutants. It’s a bit trickier with non-mRNA vaccines such as the AstraZeneca and Chinese vaccines, but it can still be done.

Will the vaccine rollout mean no more lockdowns?

The vaccine rollout should give us a much firmer handle on the spread of the virus. We can hope to stop seeing hotel quarantine workers being infected and spreading the virus outside, which is what has prompted the recent snap lockdowns in various Australian cities.

As for whether we’ll ever find ourselves in lockdown again, well, we’ll just have to wait and see. But if we’re still persisting with hotel quarantine and hosting arrivals from overseas, the vaccine program will hopefully mean we can afford to be much more liberal with opening our borders without fear that the virus will run rife.

This article first appeared in The Conversation and is republished with permission